Wells

When you are purchasing a home with a private water supply (a well), there are three key items to consider:

The well system, the water quantity and the water quality.

Well Systems

There are three common types of wells: dug, bored and drilled.

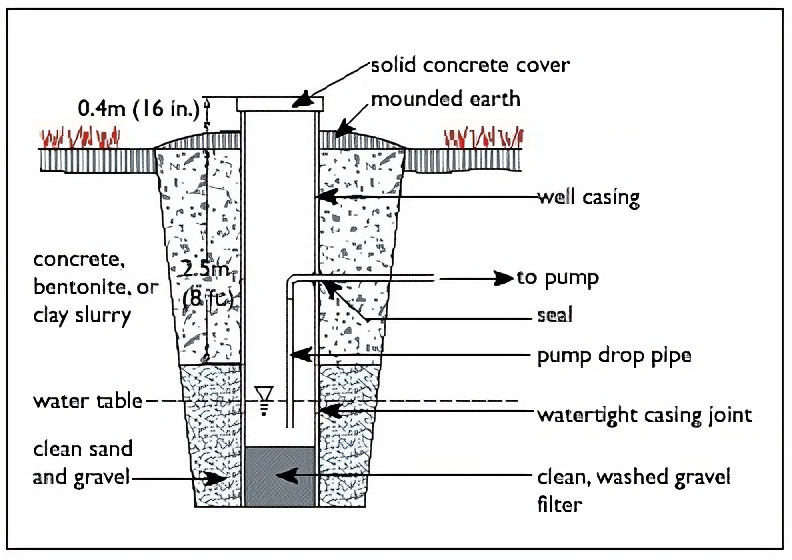

Dug and bored wells (60 – 120 cm/24 – 48 in. diameter) are commonly used to produce water from shallow surface aquifers (less than 15 m/50 ft. deep); and are prone to contamination from surface water infiltration and to water shortages (see Figure 1). An aquifer is an underground formation of permeable rock or loose material, which can produce useful quantities of water when tapped by a well. Another type of well used in surface aquifers is a sand point well (2.5 – 5 cm/1 – 2 in. diameter), which is a pointed well screen connected to a small diameter pipe driven into water-bearing sand or gravel.

Figure 1: Dug well

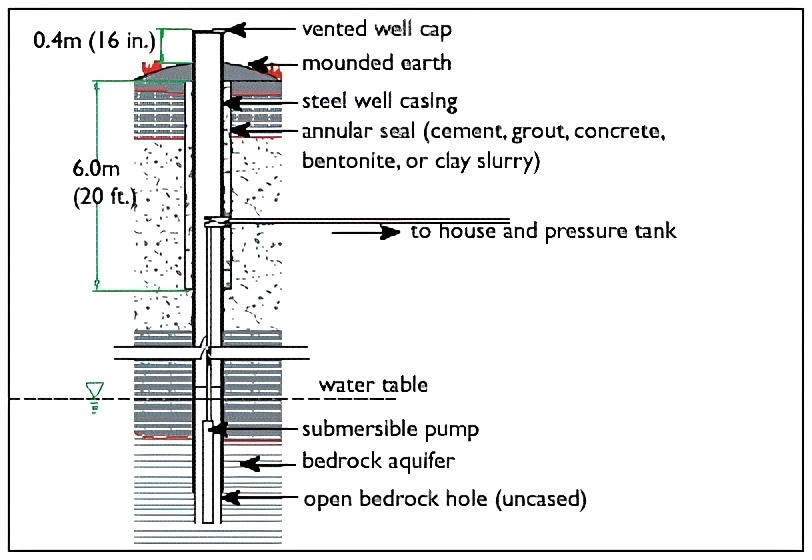

Drilled wells (10 – 20 cm/4 – 8 in. diameter) are commonly used to penetrate deeper aquifers (15 to greater than 60 m/50 to greater than 200 ft. deep), are more costly to construct, but generally provide a safer source of drinking water (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Drilled well

Common features of well systems include:

Casing – structure around the well hole, which keeps it from collapsing. It could be a steel casing, concrete rings or an open hole in the bedrock.

Inlet – allows water to enter the well from the bottom. There might be a screen at the inlet to prevent fine particles from entering the well and a foot-valve (check valve) to maintain the system’s prime and pressure.

Pumping system – includes pump, piping and necessary electrical connections to pump water from the well into the house, and a pressure tank to maintain constant water pressure in the house. Submersible pumps are usually used in drilled wells, while shallow wells usually use centrifugal pumps, which are located out of the well, most likely in the basement or in a pump house.

Surface protection – prevents surface water and contaminants from entering the well. It includes a watertight seal placed around the casing (annular seal), a well cap 0.3 – 0.4 m (12 – 16 in.) above the ground, and mounded earth around the top of the well casing to divert rainwater.

Well Inspection Checklist

The well should be inspected before the house is purchased. If there is a problem with the physical state of the well (for example, cracked seals, settled casing) contact a licensed well contractor to correct the problem. Check the Yellow Pages’ under “Water Well Drilling and Service” to find a local licensed well contractor.

Well record – Obtain a copy of the well record from the owner or the Ministry of the Environment. This should include: location of well, date of well drilling, depth and diameter of well, static water level, pumping water level, recommended pumping rate and the recommended pump setting.

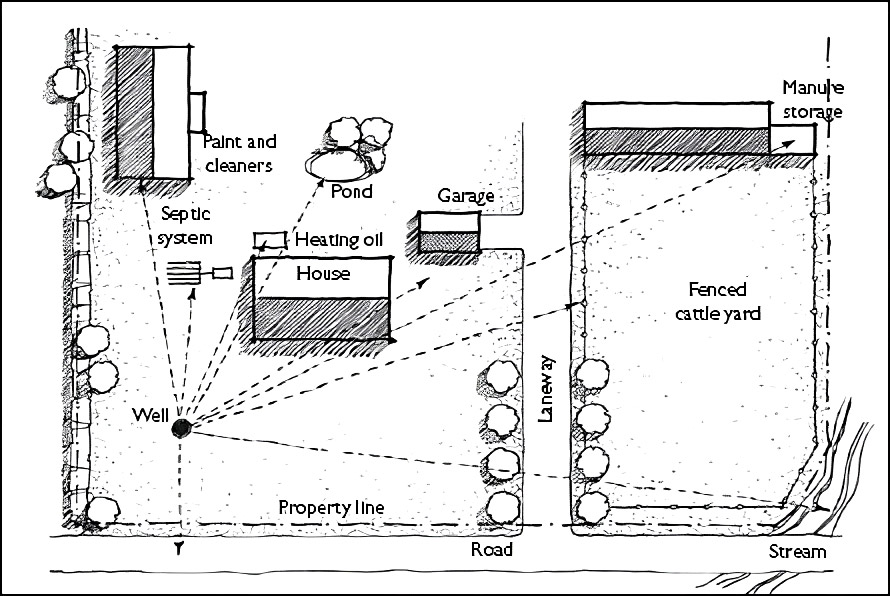

Location – A well should be located at least 15 m (50 ft.) from any source of contamination if the casing is watertight to a depth of 6 m (20 ft.); otherwise, the separation distance should be at least 30 m (100 ft.). Sources of contamination include: septic systems, manure storages, fuel storages, agricultural fields (manure or fertilizer runoff), and roads (salt runoff). Wells should be located at least 15 m (50 ft.) from a body of water (see Figure 3).

Well cap – The cap should be at least 0.3 m (12 in.) above the ground. The well cap and seal should be securely in place and watertight. A locking cap would give some added security against tampering. Well caps are on drilled wells and well covers are on dug wells. Both types should be inspected.

Well casing – No cracks or settling of the casing should be visible. The ground should slope away from the casing.

Drainage – Surface water should drain away from the well and water should not pond around the well casing.

Well pump – The well pump and distribution piping should be in good condition.

Grass buffer – A permanent grass buffer of a minimum 4 m (12 ft.) width should be maintained around the well head. Fertilizers and pesticides should not be applied to the grass buffer.

Abandoned wells – All abandoned wells on a property must be decommissioned (plugged) by a licensed well contractor. Ask the owner if there are any abandoned wells on the property and if they have been properly decommissioned.

Inside the house – Check for sand or grit in the faucet strainer which indicates a corroded well screen. Verify that the pressure tank reads between 250 to 400 kPa (40 and 60 psi). Ensure that the check valve (or foot valve) is able to sustain the system pressure by drawing no water for 30 minutes to an hour and monitoring the pressure. The pressure should not drop nor should the pump start up during this dormant period.

Figure 3: Well separation distances

Water Quantity

Wells draw water from aquifers, which are zones of saturated permeable soil or rock. Some types of soil make for good aquifers, such as gravel and fractured bedrock that can support high water pumping rates, while other types of soil make for poor aquifers, such as silty sand and clay that cannot support high water pumping rates.

Wells can run dry for the following reasons:

- The pumping rate is higher than the groundwater recharge rate.

- The water table (level of saturated water in the soil) has dropped to below the pump suction or inlet.

- The well screen has become plugged by fine sand, chemical precipitation, bacterial fouling or corrosion.

- If a well vent becomes blocked, a negative pressure may occur (in the well) during draw down and reduce or stop the pump from drawing water.

If there is a water supply problem, a licensed well contractor should be consulted. Solutions may include: water conservation in the home, digging a deeper well, unplugging a fouled well screen or replacing a corroded well casing or screen. The cost of fixing the problem should be considered when negotiating the sale price for the home.

There are three sources of information to help determine if a well can produce a sufficient quantity of water:

- local knowledge

- well record

- water recovery test

Local Knowledge

The best indication of whether there is sufficient water supply is to ask the owner, neighbours or local well drillers if there have been any problems with wells running dry on the property and in the area. Generally, shallow wells are more likely to have problems with water shortages than deep wells, as shallow wells draw water from surface aquifers, which can fluctuate greatly depending upon the amount of precipitation.

Well Record

Obtain a copy of the well record from the previous owner or the Ministry of the Environment. The pumping water level indicates if the well is shallow or deep (less than 15 m/50 ft. is considered a shallow well). The recommended pumping rate should be greater than 14 L/min (3.6 US gal/min).

Water Recovery Test

A licensed contractor can be hired to conduct a recovery test which involves pumping water out of a well and then giving it time to recharge. This can help you determine how much water you can draw from the well. A well should be able to pump 14 L/min (3.6 US gal/min) for 120 minutes or 450 L/person/day (119 US gal/person/day). Source: MOE, Procedure D-5-5, 1996.

Water Quality

The quality of the well water is very important. Poor water quality can lead to health problems, unpleasant taste and odour, costly treatment systems and/or the costly use of bottled water. Well water can be contaminated with bacteria and chemicals. Common sources of contamination include: infiltration from septic systems, manure runoff, pet waste, road chemicals as well as dissolved chemicals naturally present in the groundwater such as calcium, sulphur, chloride or iron.

Water Sampling

Your offer of purchase should always include a requirement that closing is conditional upon an acceptable water quality evaluation. It would be ideal to take three water samples, about a week apart, with one of the samples taken after a rainstorm when surface water contamination is most likely. If possible, take the water samples yourself. The three samples should be analyzed for: total coliform, E. coli, and nitrate while one of the samples should also be analyzed for: sodium, hardness, sulphate, chloride, lead, iron, manganese and pH. Ask the laboratory to indicate the drinking water standards along with the results. Additional analyses can be conducted including: metals scan, pesticides if the well is in an agricultural area with heavy pesticide use, or gasoline and solvents if the well is near a gas station or industrial area.

Contact your local public health office for instructions on where to obtain appropriate sterile sampling bottles and where to submit water samples for testing. Bacteria and nitrate are analyzed free of charge in some provinces through local public health or Ministry of Environment offices, while the additional parameters will have to be analyzed at a private analytical laboratory for a fee.

If possible, samples should be taken from a tap between the well pump and any water treatment units and/or pressure tank. Follow the directions on the sample submission form for proper water sampling procedures.

Test Results – What Do They Mean?

If concentrations are higher than the limits described below, consult a water treatment systems supplier to determine if a water treatment technology is appropriate. It is preferable to get several quotations.

Health Indicators

BLANK

Escherichia coli (E. coli) or Faecal Coliform

These bacteria are found only in the digestive systems of humans and animals. Their presence in your well water is usually the result of contamination by manure or human sewage from a nearby source such as a septic system or agricultural fields. Drinking water contaminated with E. coli or faecal coliform causes stomach cramps and/or diarrhoea as well as other problems and can even cause death. The drinking water standard for both E. coli and faecal coliform is 0 counts/100 ml. A value of 1 or more indicates that the water is unsafe to drink.

Total Coliform

This group of bacteria is always present in manure and sewage, but is also found naturally in soil and on vegetation. The presence of these bacteria in your well water may indicate that surface water is getting into your well. A total coliform value of 1 – 5 suggests that the safety of the water is doubtful, while a value of greater than 5 indicates that the water is unsafe to drink.

Nitrate

The presence of nitrate in your well water is usually the result of residential yard or agricultural fertilizers, or seepage from septic systems. Infants less than six months old can become sick from drinking formula made with water high in nitrate (greater than 10 mg/L). If you have an infant less than six months old, it is recommended to use bottled water.

Sodium/Potassium Chloride

Individuals who are on a sodium- (salt) reduced diet should consult with their physician if the level of sodium in their well water exceeds 20 mg/L. Domestic water softeners typically use sodium chloride and this increases the level of sodium in the drinking water. Potassium chloride is an alternative to sodium chloride for softening water. However, individuals suffering from hypertension, kidney disease or congestive heart failure should consult their physician prior to using drinking water containing high levels of sodium or potassium. A separate, unsoftened water supply (by-passing the water softener) can be installed for drinking and cooking purposes if sodium or potassium is a health concern.

Sulphate

At concentrations above 500 mg/L, sulphate can have a laxative effect and give a bitter taste to the water.

Lead

Lead concentrations in water are likely due to lead piping. Concentrations as low as 0.01 mg/L could cause long-term health problems.

Aesthetic Indicators

BLANK

Hardness

Hardness is a measure of calcium and magnesium in water. These elements precipitate with carbonate in boilers and pots to form scale. Hardness also makes it difficult to form lather, requires more soap, and creates a soap scum. Many homeowners decide to purchase a water softener, which replaces calcium and magnesium ions with sodium or potassium ions. Hardness (as calcium carbonate) above 80 mg/L could require a water softener.

Chloride

Chloride concentrations above 250 mg/L can give a salty taste to the water and may corrode piping.

Iron and Manganese

Well water with iron concentrations above 0.3 mg/L and manganese concentrations above 0.05 mg/L could stain plumbing fixtures and clothing; water may appear rust coloured or have black specks in it; can also cause a foul taste in the water and bacterial fouling of the well screen.

pH

pH values of less than 6.5 or greater than 8.5 may cause corrosion of piping.

Water Quality Checklist

- Water sampled on three different dates – preferably a week apart – from a tap between the well pump and any water treatment units and/or pressure tank for: total coliform, E. coli and nitrate.

- Water sampled once for: sodium, hardness, sulphate, chloride, lead, iron, manganese and pH.

- Obtain copies of previous water quality test results from the homeowner. Ask if there have been any water quality problems: frequent stomach illness (bacteria), odours (hydrogen sulphide, methane), rust spots (iron), scale (hardness), slime growth in faucets (iron or manganese), salty taste (chloride), bitter taste (sulphate).

- Review with the owner the operation and reason for any water treatment systems (water softener, disinfection system, reverse osmosis system, chlorination unit, etc.). Ask to see all treatment device operating manuals.

- Sample a glass of water for taste (salty, bitter), odours (hydrogen sulphide, methane), cloudiness (small particles) and colour (a rusty colour can indicate a high iron content). Remember you will be drinking this water every day.

- Look for scale on fixtures or around the faucets indicating hard water. Lift the lid and inspect the back of the toilet tank (the cistern) for sand, sediment, rust particles, scaling, biological growth and any other visual clues which may indicate water problems.

- Is there a “rotten egg” smell from the hot water heater? This indicates hydrogen sulphide gas, which can corrode piping.

Drilling a New Well

The cost of a new well depends on the depth of the well and the local market. For drilling and casing, well contractors usually charge a fixed rate per meter (or foot) of depth, whereas grout, seal, cap and screen installation is usually charged at a fixed rate per well.

Septic Systems

The septic system accepts wastewater from the home (sinks, showers, toilets, dishwasher, washing machine), treats the wastewater and returns the treated effluent to the groundwater. A conventional septic system is comprised of two components: a septic tank and a leaching bed.

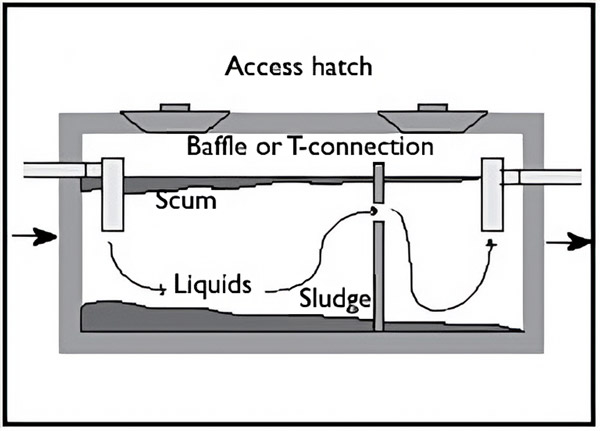

Septic Tank

A septic tank is a buried, watertight container, which accepts wastewater from your house (see Figure 4). Septic tanks can be made from concrete, polyethylene or fibreglass and in the past were sometimes made from steel (if the property has a steel tank, it is likely rusted through and needs replacing). Older tanks may be smaller than those found today (the minimum current size in Ontario is 3,600 L (952 US gal). Current tanks have two compartments, while older tanks may only have one compartment. Solids settle to the bottom of the tank to form a sludge layer, and oil and grease float to the top to form a scum layer. The tank should be pumped out every three to five years or when 1/3 of the tank volume is filled with solids (measured by a service provider such as a pumper). Some municipalities require that septic tanks be pumped out more frequently. Bacteria, which are naturally present in the tank, work to break down the sewage over time.

Figure 4: Common septic tank

Leaching Bed

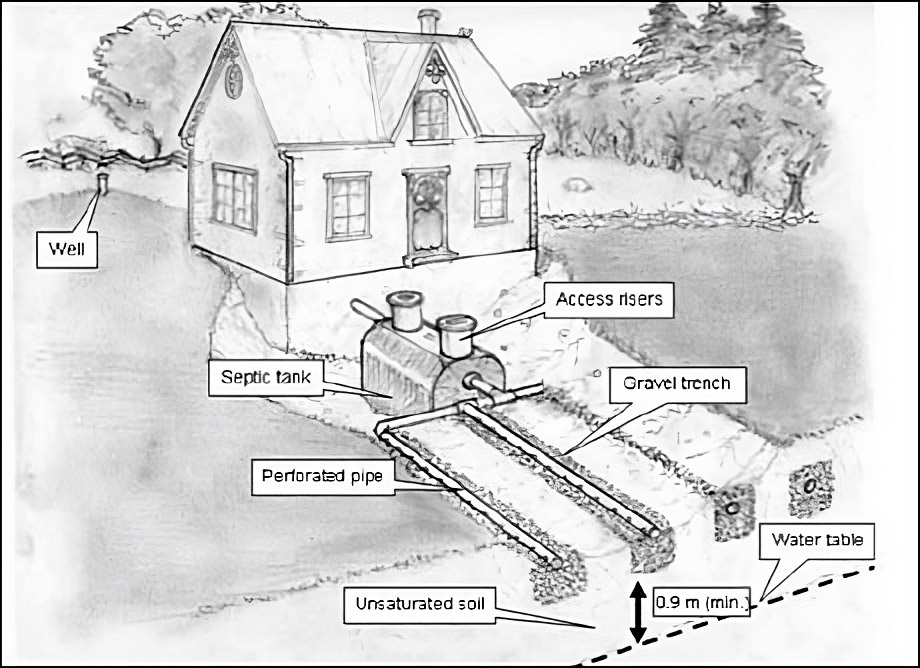

The wastewater exits the septic tank into the leaching bed – system of perforated pipes in gravel trenches on a bed of unsaturated soil (minimum 0.9 m/3 ft. – see Figure 5). The wastewater percolates through the soil where microbes in the soil remove additional harmful bacteria, viruses and nutrients before returning the treated effluent to the groundwater. In cases where there is more than 0.9 m (3 ft.) of unsaturated soil from the high water table or bedrock, a conventional system is used, where the network of perforated drainage piping is installed either directly in the native soil, or in imported sand if the native soil is not appropriate for treatment. In cases where the groundwater or bedrock is close to the surface, the leaching bed must be raised 0.9 m (3 ft.) above the high water table or bedrock. This is called a raised bed system.

Figure 5: Septic system

Credit: Eric Brunet, Ontario Rural Wastewater Centre,

University of Guelph

Inspecting the Septic System

You should have the septic system inspected by a certified on-site system professional (such as a certified installer or engineer) prior to purchasing the home. Call your local municipal office, public health office or Ministry of Environment office for a list of qualified professionals.

The inspection should include: a discussion with the homeowner, a review of the system permit, a tank inspection, a leaching bed inspection and a house inspection.

System Replacement or Repair

A septic system should last anywhere from 20 – 25 years, or even longer, if it is properly installed and maintained with regular pump-outs every three to five years.

Questions to ask the homeowner:

- Do you have a copy of the septic system permit?

- When was the last time the septic tank was pumped out? Are there records of system maintenance (tank pump-outs, system repair)?

- Have there been any problems with the septic system: system backing up, foul odours, effluent on the surface, soggy ground in the leaching bed, system freezing, toilet and drains gurgling or draining slowly?

- Have there been any potable water quality problems (E. coli, faecal coliform, nitrate)? This could be due to infiltration of the well by leakage from the septic system and could indicate a malfunctioning system. Results from the water quality samples that you take of the well water may help indicate septic system problems.

Alternative Systems

Under certain site conditions such as limited lot area, high groundwater table or poor soil conditions (clay or bedrock for example), a conventional system will not provide sufficient treatment of the wastewater. Under these conditions, it is often possible to install an alternative treatment unit. The two most common types of alternative treatment units are trickling filters, where the effluent from the septic tank trickles through an unsaturated filter media (such as peat or a textile filter), and aeration systems, where the effluent from the septic tank passes through an aerated tank.

Alternative treatment units provide a higher level of wastewater treatment, allowing the effluent to be discharged to a smaller area than in a conventional leaching bed. Effluent from an alternative treatment unit can also be discharged to a shallow buried trench, which is a pressurized pipe system 15 cm (6 in.) below the ground surface. In most provinces homeowners with alternative treatment units are required to have a maintenance contract with a service provider to inspect and maintain their systems.

ermit Review Checklist

- The septic system permit can be obtained from the homeowner or the local municipal, Ministry of Environment or public health office, depending on the jurisdiction. There may not be a permit for older systems.

- Review the system permit: age, size and type of system and separation distances (particularly from wells).

- Verify the size of the system with respect to the size of the house.

Tank Inspection Checklist

- Never enter or stick your head into a septic tank. Dangerous gases are present in septic tanks, which can be lethal, even after the tank has been pumped out.

- Compare the size of the tank and the expected water use, observe the general condition of the tank: baffles, partition wall, look for cracks and leaks. A steel tank is likely corroded and in need of replacement.

- Observe the water levels in the tank (too high suggests a clogged leaching bed while too low suggests a leaking tank).

- Have the septic tank pumped out (the owner should pay).

- Observe connections to the house and to the leaching bed (leaking pipes, crushed pipes), look for direct discharge of surface drainage into the tank. Tire tracks on the leaching bed could indicate crushed pipes.

- Clean the effluent filter (if one exists) by rinsing with an outdoor hose, allowing the rinse water to drain into the septic tank.

Indoor Inspection Checklist

- Check for leaking faucets and run-on toilets (a run-on toilet can flood the septic system). Slow moving drains and sewer-gas smells from flowing drains can indicate a failing system.

- Verify the plumbing (storm water and sump pump to ditch or dry well, toilet and sinks to septic system). If there is a direct grey water discharge (sinks and bathtub are not going to the septic system), it likely does not meet building code or health department standards. Connecting the grey water to the septic system may require the installation of a larger septic system.

- Water softener discharge: USEPA reports suggest that it is appropriate to discharge water softener backwash to a septic system. However, many jurisdictions encourage the discharge of the water softener’s backwash to a sump pump, ditch or dry well.

Under exceptional circumstances, the home may have a holding tank as opposed to a septic system. A holding tank must be pumped regularly (every few weeks) which can add a considerable expense to the household. - Inspect the sewer vent stack for damage or blockage. Simply removing an old bird’s nest might eliminate sewer-gas problems.

Alternative Systems

Under certain site conditions such as limited lot area, high groundwater table or poor soil conditions (clay or bedrock for example), a conventional system will not provide sufficient treatment of the wastewater. Under these conditions, it is often possible to install an alternative treatment unit. The two most common types of alternative treatment units are trickling filters, where the effluent from the septic tank trickles through an unsaturated filter media (such as peat or a textile filter), and aeration systems, where the effluent from the septic tank passes through an aerated tank.

Alternative treatment units provide a higher level of wastewater treatment, allowing the effluent to be discharged to a smaller area than in a conventional leaching bed. Effluent from an alternative treatment unit can also be discharged to a shallow buried trench, which is a pressurized pipe system 15 cm (6 in.) below the ground surface. In most provinces homeowners with alternative treatment units are required to have a maintenance contract with a service provider to inspect and maintain their systems.

Leaching Bed Inspection

- Check for effluent on the surface, odours, lush growth, soggy field/ saturated soil.

- Check for obstructions to the leaching bed (pavement over bed, trees in bed).

- Verify that surface drainage is directed away from the leaching bed (for example, downspouts are not saturating the leaching bed).

- Dig test pits in the tile lines for signs of ponding water and biomat (slime) growth. This indicates plugged tile lines, which may require repair or eventual replacement.

- Inspect all mechanical equipment (pumps, aerators, alarms) to ensure they are in good working order.

Contact Trevor

YOURGABRIOLA.COM

Toll-Free 1-877-422-8455

Phone 250-247-2088

trevor@yourgabriola.com

Send an instant message via email using the contact form